For the second update of 2018, I'm going to cover a more interesting aspect of the Asia-Pacific-Euro Summer School on Smart Structures Technology (APESS 2017) that I introduced in the last post, that being one of the technical site visits that we attended during the three weeks.

So, empezamos...

Given that Japan is prone to both earthquakes & strong typhoons, and has numerous densely populated urban areas, not least the Greater Tokyo Metropolitan Area which is the largest in the World, it obviously served as a more than suitable location to demonstrate some of the most state-of-the-art smart structure and structural control technologies in operation today. And well this bore true for the first of our visits, which entailed a guided tour of the interior of Japan’s largest Tuned Mass Damper (TMD) weighing a total of 1800 tons, which is equal to 6.5% of the entire structure's effective weight. It consists of 6 individual TMDs of 300 tons each and is located on the roof of the 55 story Shinjuku Mitsui Building in Tokyo (Figure 1.), to which it was retrofitted in 2015. The area is generally closed to the public, but access was permitted to the APESS '17 attendees under the supervision of our tour guide, who was also the original design engineer of the TMD system. This visit was particularly special for me, as I've had a keen interest in TMDs for quite a while now and have even wrote about one (TMD in Taipei 101) in a previous post in this blog as being an inspiration for my current path in engineering. As in the case of the TMD in Taipei 101, each of the 6 TMDs in the Mitsui Building is a pendulum-type TMD that uses the simple relationship between the mass and cord length of a pendulum to "tune" its period of oscillation to that of the structure so that when strong winds blow, the TMDs will sway out of phase to the main structure, mitigating the magnitude of vibration. Using this system of tuning means that the TMDs do not require electrical power, and so can be relied upon whatever the situation.

|

| Figure 1. Shinjuku Mitsui Building in Tokyo |

|

Figure 2. TRUSS ERSs Farhad Huseynov, Matteo Vagnoli, John

Moughty, Antonio Barrias on top of Shinjuku Mitsui Building in Tokyo, Japan

|

Figure 3. presents a photo of one of the 6 TMDs suspended from a purpose-built steel frame by 8 steel cables. The mass is positioned horizontally by four hydraulic pistons, or "oil dampers" that work to stabilize the mass and transfer its restorative energy into the structure, while not interfering with the mass itself. Figure 4. provides a more informative viewpoint of the oil dampers where it can seen how their diagonal connections help to avoid piston buckling, while increasing the TMD's range of motion.

|

Figure 3. One of Six 300 ton Tuned Mass Dampers in

Shinjuku Mitsui Building

|

|

| Figure 4. Full TMD Configuration (Hori, et al., 2016) |

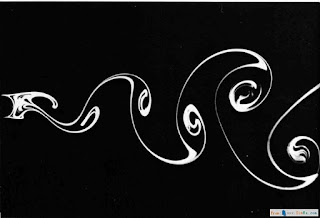

This system, or similar, is essential for exposed tall structures of regular plan, i.e. low aerodynamic design, as high winds create vortices on either side of the structure that vibrate the building in an out-of-plane manner, as shown in Figure 5. The greatest threat of such a phenomenon is when the vortices "shed" at a period close to one of the structure's first few modes of vibration, at which point resonance may occur and the probability of damage is at a maximum. In Mitsui Building's case, the TMDs were placed at the top of structure as this is the location of the maximum displacement of the first mode of vibration, and as such it is tuned to the building's first mode, which changes slightly throughout the day as people come and go for work providing additional mass in a somewhat uneven manner.

|

| Figure 5. Vortex Shedding around Cylinder (Van Dyke, 1982) |

The estimation of the wind speed required for vortex shedding to occur can be to assessed using the equation below, where the frequency of vortex shedding (f), in Hertz, is obtained using; wind speed (V), structure's diameter (D) and a dimensionless parameter known as the Strouhal Number (S) which can be adjusted to reflect the shape of the structure.

f=VS/D Eq (1.)

Usually, TMDs are only relied upon to mitigate sway in high winds, as their placement at the top of the structure can do little for violent Earthquake induced vibrations emanating from the ground, which are usually catered for by either base isolation or more strategically positioned oil dampers, as is the case in the 5th to 10th floors of the Mitsui Building (see Figure 6.). However, long period Earthquake waves can have a more global effect on a structure of this size and can cause significant displacements at roof top level and may even cause resonance to occur. For this reason the Mitsui Building's TMD system designer elected to fit multiple TMDs that are orientated off center from each other on either side of the building. This allows each of the 6 TMDs to oscillate slightly out of phase from one another when required and can also provide some torsional damping due to their position in plan (see Figure 6.).

Finally, Figure 7. presents the results of a simulated test case where the Mitsui Building was subjected to the Great East Japan Earthquake. The Results show a significant reduction in rooftop displacement, which equates to about an additional 5% damping to the entire structure (Hori, et al., 2016).

|

|

| Figure 6. TMD and Oil Dampers Arrangement in Shinjuku Mitsui Building (Hori, et al., 2016) |

|

| Figure 7. Test of TMD under Simulation of the Great East Japan Earthquake (Hori, et al., 2016) |

References

Hori, Y., Kurino, H. & Kurokawa, Y. (2016) "Development of large tuned mass damper with stroke crontrol system for seismic upgrading of existing high-rise building" International Jrn of high-rise buildings, Vol 5, no.3, pp 167-176

Van Dyke, M. (1982) "An Album of Fluid Motion" 4th Edition. The Parabolic Press, Stanford, California.